The Antifungal Property of Lupinus Mutabilis Sweet Against Phytophthora Infestans

- Sophia Yang

- Feb 16, 2024

- 4 min read

Climate change is wrecking havoc on society, but lately, it is having a more negative impact on agriculture. The current global warming phenomenon has led to a humidity increase in high-altitude places that used to be dry, so fungi hard to eliminate such as P. infestans are finding their perfect home and reproducing quickly. One of those homes is Peru, located in South America, which has a variety of crops in the hills. This country´s hills are rich in very nutritional tubers, like their principal source of food, Solanum tuberosum (potato). But, lately, its growth has been challenged due to environmental changes that bring stronger types of fungus, like Phytophthora infestans. The perfect solution for this could have been the use of pesticides or fungicides. However, this is usually unavailable for the residents due to the cost and inaccessibility. Thus, they often rely on the burning of crops. Some people rotate the plot to avoid any oomycete infection in future sowings of S. tuberosum or any other agricultural product (Ortiz et al., 1999.p. 97). However, this is becoming expensive.

Interestingly, there are few grains and tubers like the plants of Lupinus mutabilis sweet. Although they are also grown in the Peruvian hills and around fungus, they do not get infected easily. These grains are very nutritional. However, its use in the food industry is limited because it has high toxicity. Consuming this legume in high amounts can cause poisoning in humans (Villacres et al., 2008). Plus, it is bitter if not cooked well. Its mentioned toxicity and taste are positively correlated with the presence of Alkaloids in the grains and parts of the plant like the stems. Alkaloids, like β-carbolines, can cause membrane disruption in fungal cells (Wang, H. et al. 2014), lead to enzyme inhibition, damage the DNA of the being, or be antioxidants. For that reason, the presence of alkaloids in L. mutabilis sweet is why it can be considered a natural antifungal (Leyva et al., 2021).

It was proven these alkaloids could be used as an antibacterial, and antifungal in the research from the thesis of Chura called “Antibacterial and antifungal effect of tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet) decoctions on Escherichia coli and Candida albicans,” but the antifungal trait was not enough “strong,” so the control was weak. Nonetheless, the “antifungal” effects of L. mutabilis sweet can vary and be effectively strong depending on its concentration, and it has not been studied in agricultural fungi yet. For this experiment, Lupinus mutabilis sweet was used due to its high amount of alkaloids.

According to the data provided in table N°1, the species contains majority Lupanine, followed by Sparteine, and in a lower concentration 3β-hydroxylamine, 13α-hydroxylamine, and Tetrahydroromofiboline. This explains its use as a treatment alternative, achieving a fungicide, antibacterial result, and in some cases antiparasitic (Leyva et al., 2021.p.103).

Thus, the following research question was formed: Until what point do five different concentrations (0, 10, 30, 50, 100) % of the species Lupinus mutabilis sweet (tarwi) act as a natural antifungal in the species Solanum tuberosum (potato) with a controlled infection of the fungal species Phytophthora infestans?

To accomplish this experiment, a sample of the fungus acquired from an infected potato, the swab method, the decoction method, and a modified method of the diffusion agar by Kirby-Bauer was utilized.

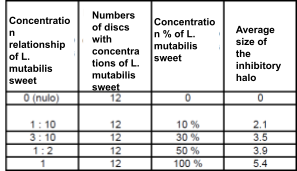

Table 2.

The concentration of L. mutabilis sweet in experimental tests and the number of samples to be used in each concentration

Table 3.

Raw data of the inhibitory halos of factors 0, 10, 30, 50, and 100% of L. mutabilis sweet decoctions on the 5th day of application.

Table 4.

Processed halo data.

Table 5.

Legend with the description of values.

Table 6.

Inhibition halo measurement scale and legend describing the values.

Table 7.

ANOVA table of the inhibition zones of the different concentrations of L. mutabilis sweet.

In this Analysis of Variance table, the values of the haloes were obtained inhibitory, through the “spreadsheets” app of the Google platform and its complement “XLMiner Analysis ToolPak”, in addition to Minitab Software. Tools that were utility to be able to find the P value and the F test, in all measurements of inhibitory haloes of each concentration used of L. mutabilis sweet. Results that will allow calculating the Tukey reliability test.

Table 8.

Tukey table with 95% reliability for the inhibitory haloes found.

For accepting whether H1 or H0, it is vital to know that:

Mean > 0.05 = accept alternative hypothesis

Average < 0.05 = accept null hypothesis

Graphic 1.

Simultaneous Tukey analysis CIs for data for a confidence of 95%

Note: If an interval does not contain zero, the corresponding means are significantly different.

Discussion

According to Table 8, the halo´s medians are 0.5538, 0.3769, 0.3469, 0.2154, and 0.0308 for the factors of 100%, 50%, 30%, 10%, and 0% . Therefore, there is a significant difference between the antifungal effect between the concentrations. For this reason, the null hypothesis is rejected, and the alternative hypothesis is accepted. However, there is zero similarity between the three factors according to Graph 1, and they belong to 3 concentrations: 30%, 10%, and 50%.

The conclusion regarding hypothesis regarding the hypothesis, table 8, and graph 1 is that a considerable antifungal effect can be obtained when 100% of the decoction is applied to the samples of P. infestans. Hence, it shows the unique letter A between all the concentrations. Nevertheless, the effect is not that different nor high when comparing the three concentrations in the table, having the concentration 30, 50, and 10% the letter C, and the median halos be not that different shown in Table 4 “processed Data.”

This means the use of decoctions of L. mutabilis sweet acts effectively as a biological fungicide, eliminating the fungus P. infestans. However, it is impossible to rule out the possibility of the fungal disease re-entering the crop after being eliminated in the first incubations. Likewise, it does not eliminate the possibility of a greater inhibitory halo effect with the use of other parts of the tuber L. mutabilis sweet such as the leaves, since they have a higher alkaloid index. (Leyva et al., 2021)

References

Ortiz, O., Winters, P., & Fanao, H. (1999). La Percepción de los Agricultores sobre el problema del Tizón Tardío o Rancha (Phytophthora infestans) su Manejo: Estudio de Casos en Cajamarca. Latin American Potato Magazine, 97–118.

Villacres, E., Peralta, E., Cuadrado, L., Revelo, J., Abdo, S., & Aldaz. R (2008). Propiedades y Aplicaciones de los Alcaloides del Chocho (Lupinus mutabilis sweet). INIAP-ESPOCH-SENACYT. Graphic Editorial. Quito, Ecuador.

Leyva, M., Quintana, E., Soto, F., Baez, K., Montes, J., & Angulo, M. (2021).Actividad antifúngica de alcaloides del extracto metanólico de Jatropha platyphylla contra Aspergillus parasiticus. Biotechnics, 22(3). http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-14562020000300100

Shijila, A., Babu, S., Anbukumaran, A., Veeramani, S., Ambikapathy, V., Gomathi, S. & Senthilkumar, G. Prospective Approaches of Pseudonocardia alaniniphila Hydrobionts for Litopenaeus vannamei. Chapter 21. Magazine Avances in Probiotics. Recovered from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128229095000216

Zavaleta, A. (2018). Lupinus mutabilis (Tarwi) Leguminosa andina con gran

potencial industrial. ed. Lima: Editorial Fund of the National University of San Marcos.

National University of the Altiplano, & Chura, H. (2017). Efecto antibacteriano y antifúngico de decocciones de tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet) en Escherichia coli y Candida albicans. National University of the Altiplano.

Crop Science (2019). Tizón Tardio de la Papa. Crop Science Argentina. Recovered from https://cropscience.bayer.com.ar/content/tiz%C3%B3n-tardio-de-la-papa

Wang, H., Zhou, L., & Yan, Y. (2014). Antifungal activity of sanguinarine and its mechanism against Candida albicans. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 69(4), 960-967.

.png)

Comments